Invisible problems are often the most difficult to understand and address. They remain unseen not because they do not exist, but because they are seldom openly discussed. One such issue is sexual abuse against children and the abundance of sexualised or abusive content online. Adults do not always consider this issue or monitor it closely; asking questions about this aspect of life is hard, and hearing the answers could be even harder. However, silence does not mean safety; it means vulnerability.

Reprinted from Dzerkalo Tyzhnya.

When Ukrainian sociologists started studying children’s experiences online, the results were not just alarming — they were shocking. It turned out that exposure to disturbing or traumatic content is not an isolated occurrence, but a part of everyday life for many children. Violence, scenes of destruction, military actions, and cruelty toward humans or animals — all of this appears in children’s social media feeds.

Sexualized content is a particularly troubling aspect of the problem. According to the study “Sexual Abuse Against Children and Sexual Exploitation of Children Online in Ukraine”,40% of surveyed children are regularly exposed to sexually explicit images or videos. 13% reported they saw such content featuring people they personally know. Every third child has, at some point, faced inappropriate questions, requests for intimate photos, or even in-person meetings with strangers from the Internet.

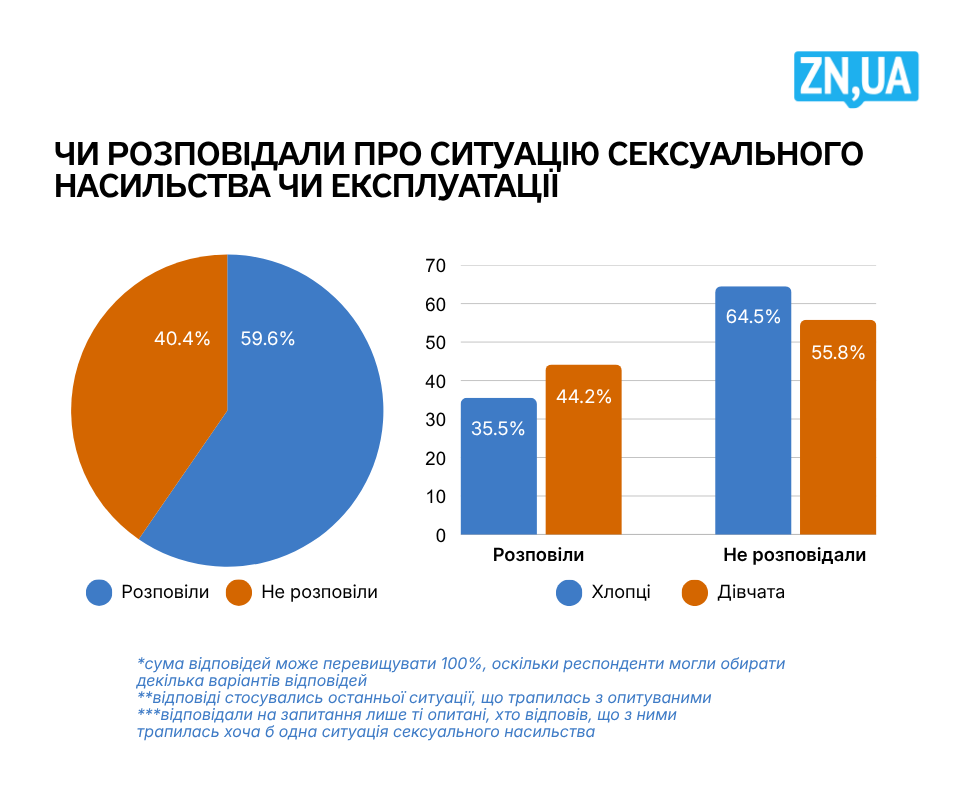

The most disturbing statistic pertains to silence rather than the number of views or messages. Only 27% of children who have faced threats or attempts to make their intimate photos or videos public have reported such incidents to an adult. About 60% do not tell anyone about what they have seen or experienced. If they do share, it is mostly with peers. However, friends are not always in a position to help. At the same time, parents and adults are often unaware that their child has gone through or is going through such an experience.

From the film Caught in the Net

This silence is not accidental. It is one of the key strategies that criminals and predators rely on when targeting children through social media. Children remain silent because they are afraid, ashamed, unsure of how to explain what happened, or convinced no-one would believe them. Adults, on the other hand, stay silent for different reasons, believing that “this rarely happens,” “this doesn’t concern my child,” or “this is happening somewhere else, not here.” Unfortunately, the data tells a different story: this is not an exception, but a reality for a significant number of children and adolescents.

According to sociologist Olha Ovchar, Director of the research agency Proinsight Lab, which conducted the survey, nearly every child on the Internet is almost guaranteed to encounter so-called “disturbing content.” This includes not only scenes of violence but also information about self-harm and sexual content that children are not actively searching. Moreover, the amount of time children spend online continues to increase. Due to online learning and the overall security situation in the country, many are forced to stay at home. Survey data shows that three out of four children spend more than three hours online every day. Fewer than 2% of children spend less than an hour online.

In reality, silence means not just a lack of trust or communication — it is also a reflection of uncertainty. Sociological data shows that, even when children receive direct threats or inappropriate offers online, many simply block the sender and take no further action. About 28% do not even do that. This is not necessarily because they are unwilling to act, but because they do not know how to respond appropriately or do not consider it important enough. According to a 2025 survey, 59.6% of respondents never told anyone what happened. Among those who did speak up, the vast majority (83.4%) confided in a friend; about a half informed their parents or other adult relatives (32.5%); and less than 10% turned to a trusted adult (9.4%), a teacher (4.5%), or a psychologist (3.6%).

Chart: ZN.UA

This invisibility puts us into the invisible risk zone. However, silence does not offer protection — it merely allows violence to become more subtle and normalized. If we hope to make any change at all, we must start with a conversation by acknowledging the problem and finding ways to truly listen to one another.

“We hear children far too rarely,” says Mariana Hevko, psychologist and one of the few specialists in Ukraine working specifically with children and adolescents who have experienced violence. She not only supports them in her office, but also accompanies them during interrogations and in court, quite literally holding their hand through the most difficult moments. Mariana understands all too well how hard it is for children to talk about what has happened to them. She also works as an expert for the public information campaign “Sexual Abuse Online: How to Protect Children,” run by the DOCU/CLUB Network of the NGO Docudays.

“Very few children actually reach out for help. Most of them encounter content or individuals that make them feel uncomfortable, yet choose not to talk about it with adults. This is one of the most urgent and painful issues,” she acknowledges. However, she also notes that this situation is not unique to Ukraine — unfortunately, it is a global trend.

Mariana Hevko

Power imbalance and the role of adults.

According to Mariana Hevko, the main reason for children's silence lies in the very nature of abuse: it is always about a power imbalance. “The child is already in an inferior position compared to the perpetrator. This is not about equality or the ability to protect oneself. Intervention must come from someone stronger. But adults can only help if they are aware of what is happening. Finding out about it is often difficult, because the child tries to conceal their experience,” she explains.

This is particularly true for adolescents aged 11-12, who consciously try to conceal what they are going through. However, much depends on the child’s relationship with adults. Children are more likely to open up to those they trust, for instance, a psychologist, teacher, or coach. They hardly ever confide in their parents, though.

Why won’t children confide in their closest ones?

There are various reasons for children's silence. In part, it reflects a global trend: children are generally reluctant to share uncomfortable experiences with adults. However, in Ukraine, several additional factors make the situation even more complex.

First and foremost, there is a lack of systematic educational outreach. “Ukrainian children receive very little information about what constitutes inappropriate behavior, how to recognize it, or where to turn for help. At the same time, many adults, who have been raised in a culture of tolerance for intrusion into personal space, cannot fully grasp the importance of respecting personal boundaries. At best, they tell children, ‘You can turn to the police.’ But the police do not always respond appropriately, especially when the case involves teenagers who may, for example, have been intoxicated or are viewed by society as ‘troubled,’” explains Hevko.

All too often, adolescents face judgment even from those who are supposed to protect them. This erodes their trust in adults in general. Most cases become known not from children’s reports, but rather from social media monitoring or from intervention by other adults.

Photo from open sources

A culture of tolerating violence.

Mariana Hevko shares examples from her practice. “There was a case where a girl was beaten. She didn’t file a report, though; the police found her through social media. At first, she refused to press charges because she believed it was her own fault or thought the perpetrator would change. Very often, children do not identify violence as something that must be stopped. In our society, it is often treated as normal. ‘Teenagers got into a fight? Well, just stay away next time, it happens’ — that’s what adults say. This is what a culture of tolerating violence looks like.”

As a result, children develop a distorted understanding of what is acceptable. They may not always realize that what happened to them was wrong, or that they have the right to speak about it openly. “Children often do not realize what is okay and what is not. The adults themselves are not always able to clearly communicate those boundaries. The sexualisation of children in everyday life is also common. For example, a 12-year-old girl is taken for cosmetic procedures, sent to the gym for body sculpting, and put on a diet during a time of intense hormonal change. This fosters objectification of the body. And all of this is widely accepted by society as the norm.”

Family-related reasons for silence.

There are also more personal, psychological reasons for a child’s silence. These reasons may seem simple, but are, in fact, very common. “Many children are afraid of disappointing their parents. They feel ashamed and don’t want to see shock, sadness, disgust, or pain on their mother’s or father’s face. Even if the parents are loving and open, that alone does not guarantee that a child will come to them with their problem,” psychologist Mariana Hevko emphasizes.

Individual traits, such as self-esteem, confidence, and awareness, also play a role. But the central factor is almost always fear. This may be fear of punishment (if the child broke a rule), fear of being dismissed (“this isn’t a big deal”), fear of shame (“it’s too hard to talk about”), or fear of exposure (“what will others at school think of me?”).

Another powerful factor is intimidation by the perpetrator, or the “predator,” as such offenders are often called. “Threats and blackmailing are highly effective, forcing a child to remain silent,” says Hevko.

Photo from the film Caught in the Net

Sexual abuse is an urgent issue.

In cases of sexual abuse, a child's silence is often ensured through a deliberate and manipulative process of “grooming.”

“This is an extremely dangerous pattern. The perpetrator builds a relationship of trust with the child, one that is labeled a ‘secret.’ These online predators will say things like, ‘This is just between us,’ or, ‘No one will believe you anyway.’ As a result, the child takes the blame upon themselves,” explains psychologist Mariana Hevko.

This tactic is particularly effective with younger children or adolescents whose critical thinking skills are not yet fully developed.

Is there a way out of this silence?

According to Hevko, even in the most perfect relationships between parents and children, it may not be possible to fully overcome this silence: “Parents could do their best, and yet the child may choose not to tell them, simply because he or she doesn’t want to hurt them. That’s why building and maintaining trust is important. We also need to admit that children may choose to confide in another adult, and that is perfectly okay,” she says.

The key strategy lies not only in a family-level engagement, but also in a systemic response. “Children need to stay in contact with other adults, including teachers, coaches, and psychologists. These adults must be safe, consistent, and attentive. Only then can a child feel safe enough to trust them. Sometimes it’s easier for a child to open up to a neutral adult at school who reacts calmly and considerately. This is precisely why our film club network screens the documentary Caught in the Net by Vít Klusák and Barbora Chalupová. It helps adults understand how predators operate online, manipulating and preying on children. We teach parents and educators how to become ‘safe adults’ and protect children from sexual abuse on the Internet,” Hevko concludes.

Photo from open sources.

What does it mean to be a “safe adult”?

It is not about being friends with a child. “An adult must remain an adult, because a child needs stability and support. Safe adults are able to explain their reactions, refrain from judgment, and listen carefully. Most importantly, they do not make promises to keep secrets when the child’s safety is at risk,” emphasizes psychologist Mariana Hevko.

She explains that adults are liable to report such incidents. However, this must be done carefully, by discussing the child’s fears, explaining what will happen next, and why it is important.

Is there any progress?

Despite the challenges, Mariana Hevko sees optimistic positive signs. “Today’s generation of children is braver. They are more assertive in defending their boundaries. There are some positive dynamics. The number of reports to the police is increasing. More and more often, children are turning to teachers and neighbors rather than parents. This doesn’t mean the problem is solved. Many children still lack access to this kind of information or don’t even realize that their experiences are unacceptable. But there is a shift,” Hevko concludes.

What is the solution?

What can a child or teenager do if they find themselves in a situation involving abuse, when speaking to their parents feels impossible and there is no “safe adult” by their side? In Ukraine, there are resources that can serve as a lifeline in such situations. One of them is the StopCrime portal, developed by the NGO “Magnolia” with the support of the Ministry of Digital Transformation of Ukraine and the Cyber Police Department.

This is a platform where harmful content, online sexual abuse against children, and other crimes involving minors can and should be reported. Reports can be submitted anonymously by adults or children themselves. “Even when a child appears to have a trusting relationship with adults, they may still be too afraid to speak up — out of shame, fear, or simply not wanting to ‘make things worse.’ That’s why it’s essential to have an alternative, a space where the truth can be told without revealing one's identity,” explains Oleksiy Sydorenko, Head of the Child Protection Program at NGO Magnolia.

1,538 reports in six months.

This is the number of reports regarding child sexual abuse materials that were submitted in the first half of 2025. On average, that amounts to eight to nine reports per day, and these are only the cases that were successfully identified.

“Of these, 812 contained confirmed signs of a criminal offense. 503 were hosted on servers located in Ukraine, and we forwarded them to the Cyber Police Department. Another 309 were hosted in other countries, and we shared the information with international partners via the InHOPE network,” says Oleksiy Sydorenko.

Photo from open sources

40% of all reports are submitted by Ukrainians via the StopCrime Portal. The remaining reports are submitted by analysts from international hotlines in countries such as Spain, France, and Germany, when they discover that the harmful content is hosted in Ukraine.

“The InHOPE international network comprises hotlines from over 40 countries. For example, if an analyst in France identifies harmful content hosted in Ukraine, they pass the information on to us, and we do the same for them,” the expert explains.

A disturbing trend: a surge in explicit content featuring adolescents. In recent months, analysts have observed a growing number of cases involving nude adolescents aged 10 to 14, posing in front of a camera, seemingly following instructions. “It appears as if someone off-screen is directing the child, telling them how to pose and what to show. All of this is happening in livestream mode,” says Sydorenko. According to him, the share of such incidents has increased by 15–20% compared to previous months.

The number of people calling the hotline increases every year. “The surge in the number of reports doesn’t necessarily mean that crime rates are growing,” says Oleksiy Sydorenko. “I believe it’s due to the increased awareness about the hotline itself. More and more people are learning about the existence of this service in Ukraine. As for the real scale of these crimes, we can only speculate. Only a small fraction ever gets reported. Before our hotline became operational, the international InHOPE organization ranked Ukraine among the top three countries with the largest volume of hosted content depicting sexual abuse.”

Just because a child remains silent does not mean they are safe. The invisibility of abuse is one of its most harrowing forms. That silence must be broken with words of support, acts of help, and consistent attention and care. Responsible adults should not turn a blind eye; they should explain, listen, build trust, and teach children to speak openly.

Today, Ukraine is fighting on multiple frontlines. One of them is the safety of our children in the digital world. In a country ravaged by war, where homes and boundaries are being destroyed, remaining silent about such crimes means allowing them to continue. Our children deserve protection. They deserve the truth. And they deserve to know that the adults by their side won’t look away.

Who to contact?

StopCrime Portal — stopcrime.ua. Anonymous reports of any crimes against children, including sexual abuse on the Internet. Analysts will verify the facts and forward the data to the police.

La Strada NGO Hotline — 116 111. HelpLine for children with psychologists. All calls are free of charge and anonymous.

These reports are only for confirmed cases of sexualized depictions of children or abuse against children. However, there are also numerous reports on other forms of abuse, including cyberbullying, battering, psychological pressure etc. In such cases, StopCrime will forward the report to the National Police or child services, depending on the offense.

Written by Yaryna Skurativska

The development of the DOCU/CLUB Network is funded by the Embassy of Sweden in Ukraine, the National Endowment for Democracy (NED), and Fondation de France.

The opinions, conclusions or recommendations are those of the authors and compilers of this publication and do not necessarily reflect the views of the governments or charitable organizations of these countries. The authors and compilers are solely responsible for the content of this publication.

All news